Why modern Simrans are giving up on Raj | India News

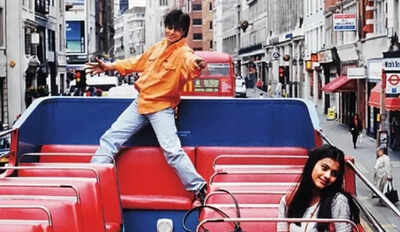

Thirty years of ‘Diwale Dulhania Le Jayenge’, the film that invited a subset of urbane women to ‘come fall in love’. My qualifications to trace its journey involve being an accidental chronicler of the economics and mathematics of Shah Rukh Khan and his female fans. For fifteen years, I thought I was interviewing women about how they saw Khan. Instead, I discovered how these women saw themselves and their frustrated attempts to find love and livelihoods.Finer minds than mine have dissected every inch of the film; there is thirty years of discourse out there. Stunning photographs of audiences at Maratha Mandir signal how the film continues to offer escape from the drudgery of daily life. For parts of the commentariat, the romance of Raj and Simran captures India’s enduring love affair with patriarchy and caste endogamy. After all, Simran can only marry Raj if her father approves. Raj prefers patriarchal permission games to the rebellion of elopement. Familial regulation of women’s bodily autonomy remains at the heart of the plot. None of the women in the film seem to have jobs beyond loving andcaring for men. Simran writes great poetry but possesses no clear profession. Her girl gang and Europe trip looks fun, until a group of entitled boys crashes into it. Raj most certainly meshes harassment with wooing.The film marks the beginning of elite Indians awkwardly managing the pretense of modernity. In post-liberalisation India, with candy floss and GDP growth in the air, here is the fusion of traditional rituals, wealth and retail consumption.So, in its thirtieth year, what does DDLJ mean? I am not brave or foolish enough to make summary pronouncements on how most, or even many women feel about the film. DDLJ may be one movie, but each of us has experienced it in our own unique way. Some of my closest friends have grown up to be cynical about the love story. “He will grow old to be an unhelpful unsexy Uncle”, they say. They surmise that Simran would be better served by revolution than Raj. Others continue to prefer the promise of Raj’s wideopen arms and sanskari happy endings.For some elite urban women like myself, the film is a reminder of the years spent in the captivity of romantic love, hoping to find the One. We were foolish and privileged when we watched DDLJ as teenagers; we are foolish and privileged in our forties. For women our age from the precariat, it was often the first film they recalled watching in a hall or a screening at home or their neighborhoods. Songs from the movie haunted my fieldwork across India; homebased women workers I surveyed had memorised the film’s beautiful soundtrack.Aditya Chopra fashioned a new masculinity through Khan. He raced airplanes, cried beautiful tears, fasted for karwa chauth, broke Preeti’s heart, helped women with housework and sarees. In the second half of the film, Raj transforms into a man who performs emotional and care labour with elegance and elan. Dialogues were equally proportioned between men and women, a rare event in Hindi films.One scene seemed to stir every fan I interviewed. It involved Simran’s mother remarking on how men would never sacrifice their well-being, while women were expected to give up their desires without complaint. She urges the young couple to run away. Simran is willing and raises this option repeatedly, Raj declines. So many women would wonder about Simran’s fate. If she gave up on Raj or gave up on the protection of her family home — where would she go? Would she risk an honour killing? Could she find safe housing? Could she afford to live on her own? Could she bear the loneliness of her revolt? Would the state or market offer credible protection?Since DDLJ’s release in 1995, the times have certainly changed for women, as has the economy. However, the binding constraints on Simran’s horizons remain the same. In 1994, 23% of urban women held paid jobs or were looking for work compared to 80% of urban men. In 2024, the gap remains significant — 76% urban men participated in the labour force compared to 28% women. Public space and the housing market remains odiously masculine. Rates of domestic violence suggest the home is deeply unsafe. Ten percent of our police force is female.A young home-based worker I followed, with a brief history of running away from home, insisted that elopement was the easier choice for men, more so when their fam-ilies supported the match, as was the case in DDLJ. Since intimate violence was assumed as a fact of life, women would always need a safe place to escape. I heard the same explanation from a posh Rajput woman in an abusive marriage. Abandoning the family would make Simran’s ‘fall back’ position weak. Projecting their precarities onto the film’s couple, these women understood Raj as securing Simran a way home should their marriage fall apart. Where earlier all I saw was capitulation and conformity, I began to see bargains and trade-offs. I started to realise that the calculus of rebellion can look very different for women. There are days when a clumsy regressive Raj feels better than liberal men who find no greater joy than lecturing ladies without ever comprehending our bitter constraints.DDLJ marks three decades of women’s complicated relationship with their own freedom, the conformist compromises forced upon some, while happily chosen by others. But much like Simran’s mother, I’m impatient now. I have long given up on Raj, the belief that a handsome man can offer happiness. I prefer a political regime that prioritises liberating Simran to fall in love with her own possibilities. I long for the romance of public institutions that credibly care for women’s safety and safety nets. Raj can wait. Come fall in love with your freedom. Jee lete hai apni zindagi.Bhattacharya is an economist and author of ‘Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh’