Earth’s largest camera will sweep the sky like never before

A top a mountain in Chile, where the days are dry and nights are clear, a team of scientists and engineers is preparing for one of the most important astronomical missions in recent times. Among them is Kshitija Kelkar, whose life has taken an interesting turn.Twenty years ago in Pune, the city she’s originally from, Kelkar sent a photo of a lunar eclipse she had taken with a digital camera to Sky and Telescope , a popular astronomy magazine. The publication accepted the photo and released it on its website under ‘Photo of the Week’.

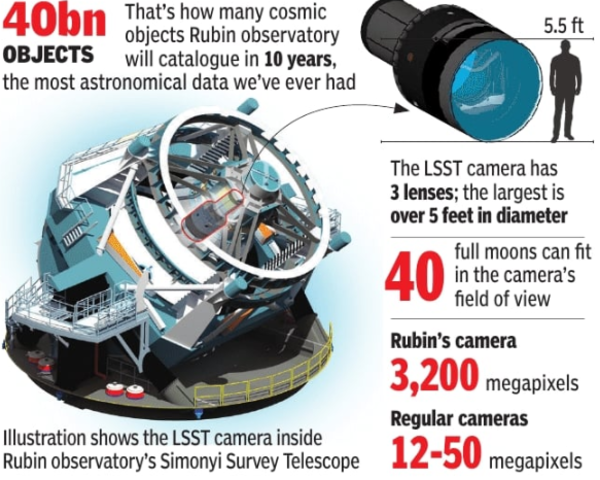

Inspired, Kelkar would turn astronomy into a career, and after degrees from Fergusson College, Pune University, University of Nottingham and doctoral work on how galaxies transform in their clusters, she arrived in Chile on a grant to use telescopes for her research.Today, years after that photo she took on a tiny camera, she’s an observing specialist at the Vera C Rubin Observatory, looking at the sky through the largest digital camera ever assembled.On June 23, that camera released a set of photos that stunned astronomers. Caught in unprecedented detail were galaxy clusters, distant stars and nebulae. In one photo, the camera — the size of a car with a resolution of 3.2 gigapixels — snapped a nebula around 4,000 light years away.The Rubin observatory could even save Earth. In May, within just 10 hours, it found 2,104 previously undetected asteroids. Since its telescope takes images in quick succession, it’s able to catch moving objects from the crowd of stars in the background that tend to stay in place. If even one space rock is headed our way, chances are first alerts would come from Rubin.Humanity does have other powerful telescopes. There’s James Webb, for instance, 1.5 million kilometres away from Earth with its own very dark sky. But it’s mainly for zooming into specific targets. There’s James Webb’s predecessor, Hubble, currently in orbit over 500km above Earth. In 1995, it took Hubble nearly a week of long exposure to generate the now-famous Hubble Deep Field image, which showed about 3,000 very distant galaxies.The Rubin Observatory, during its first test run in April, generated an image that revealed 10 million galaxies, in a matter of hours.Part of the reason why it could do that is its very mission. Unlike James Webb and Hubble, which take in small parts of the sky, Rubin is a survey telescope, which means it shows the entire big picture, not specific objects. An image it takes covers a swathe of sky equivalent to 40 full moons — Webb’s cameras show a size lesser than a full moon. A single photo from Rubin is so large, one would need 400 ultra-HD TV screens to see it in its full glory.

Large is ideal, given Rubin’s purpose. Its primary optical instrument, named Simonyi Survey Telescope, is set to embark on a 10-year project called the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), to map the visible sky in extraordinary detail. The telescope is more than 300 tonnes of steel and glass, which is regularly cleaned using CO 2 . Over the next decade, this telescope and the giant LSST camera will take photos of the southern hemisphere sky, every 3-4 nights, to create the largest time-lapse film of the Universe ever made.Why time-lapse? Imagine you’re on the terrace of your building with a camera pointed at your neighbourhood. Time-lapse would reveal the windows that opened, the lights that came on, the cars and curtains that moved and the doors that opened.Rubin observatory will do that to the Universe, find new objects and previously unknown interactions between them. “We’re going to be continuously taking 30-second images all night in different filters,” said Kelkar. “And since we’ll be observing the night sky every 30 seconds, in two back-to-back images of 15 seconds each, we’ll catch any object that has changed its position or brightness.”These objects may be stars, asteroids, unnamed comets and even potential sources of gravitational waves. This is where Kelkar said it would be unfair to compare Earth’s telescopes — they’re meant to complement each other, not compete.Scientists, amateur astronomers and space enthusiasts the world over can sink their teeth into this data. “People once thought the Earth was at the centre of the system. But then someone came along and said ‘no, it’s the Sun’. Similarly, we may find something absolutely mind-boggling, even evidence of life elsewhere,” Arvind Paranjpye, director of Nehru Planetarium in Mumbai, said.Kelkar has been at Rubin for over a year, living in the town of La Serena — a twohour drive away. Her commute to work is through scenic valleys and along the ‘El Camino de las Estrellas’, or the ‘Route to the Stars’, because of the number of astronomical observatories along the way.The route also needs light discipline, which means those driving there after dark cannot really use full-beam headlights. “We usually have our hazard lights up,” said Kelkar. At the observatory, work begins shortly before sunset. After a check of all systems, by Kelkar and the rest of the observing specialists, they open Rubin’s massive dome for night operations.The observatory’s placement atop the Cerro Pachón mountain puts it well above the localised turbulent layer where warm air mixes with cooler air from above, offering a clear view of the stars.Right now, trials are on as crews perform final checks before Rubin, 20 years in the making with $800 million in construction costs, formally begins its survey later in 2025.The Legacy Survey of Space and Time will be of unprecedented scale.Remember that image Rubin released of 10 million galaxies? Well, they make up just 0.05% of nearly 20 billion galaxies the observatory will have imaged when LSST ends in a decade. Rubin may see millions of distant stars ending in supernovae and into new reaches of our own Milky Way galaxy.Some 10 million alerts to scientists are expected from the observatory every night — whenever a change is detected in the series of photos it takes. Software will automatically compare new images with the stack of older ones. If an object has moved in those photos, flashed, exploded or streaked past, the software will detect the changes and dispatch an alert, all within minutes.There’s no other telescope that can do these things — detect real-time changes in the immediate sky and flashes of light from distant objects, and at such scale. In just one year, Rubin observatory will have detected more asteroids than all other telescopes combined.There’s more. The Simonyi Survey Telescope, set up on a special mount, is also fast. It can quickly swivel from one wide area of sky to another — within five seconds.Nothing will miss this allseeing eye. Kelkar said word has already been sent out to experts worldwide to investigate the 2,104 newly detected asteroids. “The telescope will be a game-changer,” she added, “because we’re giving a common dataset for all kinds of science at once. We don’t need specialised observations. It’s one data for all.”Kelkar was in the control room at La Serena when the first images landed.“Twenty years of people’s professional lives had come down to that moment. We’re about to make a 10-year movie of the night sky, with the fastest telescope and the biggest camera ever made. It’s going to be fantastic,” she said.LAST WEEK ’ S QUICK QUIZQuestion on June 30: Challenging the belief that oxygen is produced only through photosynthesis, scientists have found polymetallic nodules deep in the ocean producing oxygen. What’s this oxygen called? Answer: It’s called ‘dark’ oxygenEarth’s Largest Camera Will Sweep The Sky Like Never Before