Why solar-powered prosperity in Thar desert is a mixed blessing | India News

Rajasthan’s Thar desert is glowing with solar panels, powering India’s clean energy dreams. But behind the boom lies a quieter story that goes unsaid — of vanishing camels, felled khejri trees, and fading pastoral lifeThe Thar desert is dancing, but not to the tune it once knew. Ever since Barmer struck oil in 2004, the desert was catapulted from obscurity to the frontline of India’s energy story. Solar fields — in neat military lines — sprawl where flocks once grazed, and a Rs 80,000-crore crude refinery waits in the wings. Jaisalmer, once a sepiatinted tourist postcard of camels and its famous fort, is adding cement to its desert identity. Prosperity has found a new postcode, dragging people from the margins to the mainstream.Yet, beneath the sheen of progress, another story simmers: of cultural identity of its people and centuries-old pastoral traditions fading, camels and sheep disappearing, vital khejri trees falling to the axe, and the fragile biodiversity fraying. The region is at a crossroads, caught between progress and preservation, megawatts and memories.

Solar rush, sore communitiesIn Jodhpur’s Bhadla panchayat, Sadar Khan recalls when the 25,000 acres of govt land around his village were still pasturelands — grazing grounds for sheep, goats and cows. That changed in 2014, when the govt carved out 14,000 acres for a mega solar park. “I had 250 animals once. With no pastures left, I had to sell. The few I keep now are only to remember who we were,” he says, pointing out to the blue sea of solar panels that occupy the horizon.But the development has been lopsided, says Khan. “The park brought in investment of about Rs 10,000 crore, but we do not have a doctor, nor a school offering classes beyond class 8,” he says.Solar plants have also mushroomed across Jaisalmer, Bikaner and Barmer. For investors, it’s a dream run: secure a power purchase agreement (PPA) for 25 years, instal panels, and enjoy stable returns without much operational hassle. For villagers, it has meant leasing out one-crop or unproductive land for Rs 30,000 an acre, annually. But there are hidden costs. Lakhs of khejri trees were felled, ponds and sacred groves levelled, and grazing lands erased.

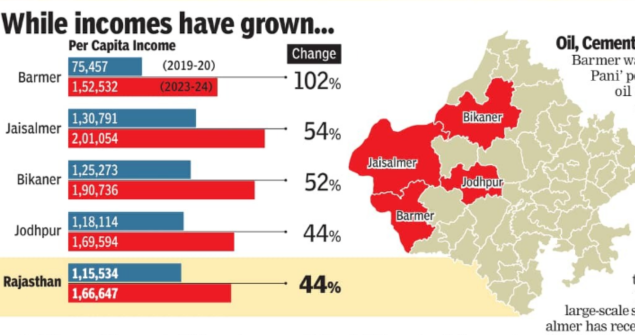

Fight for land and beyondFor men like Sumer Singh Bhati and his community of herders and farmers, this is not just land, it is also identity. Supported by thousands from Jaisalmer, Barmer, and Bikaner, Bhati has rallied against the large-scale diversion of pastureland and sacred groves — “orans”, in local parlance. “We are not against development, but against the erasure of our ecosystem and culture,” Bhati says. On Sept 26, nearly 15,000 villagers marched in protest, with a sit-in at the Jaisalmer collectorate. The struggle is about ‘ jeevika ’ (livelihood) and ‘ pehchaan ’ (identity), Bhati says. The protest was called off on Oct 19 after the govt assured the protesters that 8,000 acres of community forest land would be notified and safeguarded from destruction, with no allocation for solar or cement projects. However, Bhati said they had also submitted a separate proposal seeking protection for an additional 80,000 acres of community forests, which remains pending at the collectorate level. “We will resume our protest if the 8,000 acres are not formally declared as a protected area,” he said.Economy’s leap, ecology’s slideThe desert economy once revolved around livestock — camels, cattle and sheep. But their numbers are dwindling rapidly. The 2019 livestock census showed a 13% fall in sheep and a 35% decline in camels. Professor Anil Kumar Chhangani of Bikaner’s Maharaja Ganga Singh University warned the numbers today would be far worse. “If the census were to be conducted today, the numbers could be appalling. Besides the rapidly falling animal population, about 25 lakh khejri, ker, kumta, jal and rohida trees — central to the Thar desert’s biodiversity — have been felled,” Chhangani claims.The last known census of khejri trees ( Prosopis cineraria ), Rajasthan’s state tree, was conducted by the Central Arid Zone Research Institute in 2015. This study across 12 dry districts, such as Jodhpur and Nagaur, found the density had fallen to fewer than 35 trees per hectare from about 90 in the 1950s and 60s. The institute attributed the decline to groundwater overuse, fungal attacks, and land development.Recently, Bikaner’s master plan has proposed to convert 27,000 bighas (625 acres) of pastureland into commercial and residential use. “Pastures are oxygen for animals, birds, reptiles, and people. Sacrificing them is ecological suicide,” Chhangani cautions.Oil, cement, solar, rising incomesBarmer was once dreaded as a ‘Kala Pani’ posting for officials. Today, oil and thermal power have turned it into an emerging economic frontier.Its per capita income — Rs 1.5 lakh per annum in 2023-24 — doubled in the past five years, nearing the state average of Rs 1.7 lakh. Jaisalmer, Bikaner and Jodhpur, too, boast incomes above the state average. Besides being home to large-scale solar and wind farms, Jaisalmer has recently attracted investment of Rs 18,000 crore in the cement sector, spanning seven plants. In Pachpadra, a Rs 80,000-crore refinery is set to start commercial operation, promising to change the region’s future forever. With 40GW (1 gigawatt = 1,000MW) of solar plants already installed and another 50GW planned, much of it in the desert region, Thar’s development is reaching for the skies, promising more prosperity.Balancing sun and sandRajasthan accounts for India’s largest solar power capacity, at 20%. It is critical to the country’s global climate commitments, and the target of 500GW by 2030. But the question is not whether solar is important, it is about saving the desert’s soul: its trees, animals, and the pastoral life it is proud of.Chief minister Bhajan Lal Sharma promises to plant 10 saplings for every khejri tree that is felled. But people like Bhati and Khan dismiss it as tokenism. Replanting cannot replace centuries-old groves or restore lost pastures, they say.